After stroke, you will probably experience problems with trying to recover your balance (your ability to control your body without movement against gravity) and stability (your ability to control your body during movement).

Your stroke will have weakened the messages your ears, eyes and muscles send to your brain. These messages are essential to initiating and maintaining balance, and they work together automatically and subconsciously so you’re usually unaware of them unless something goes wrong.

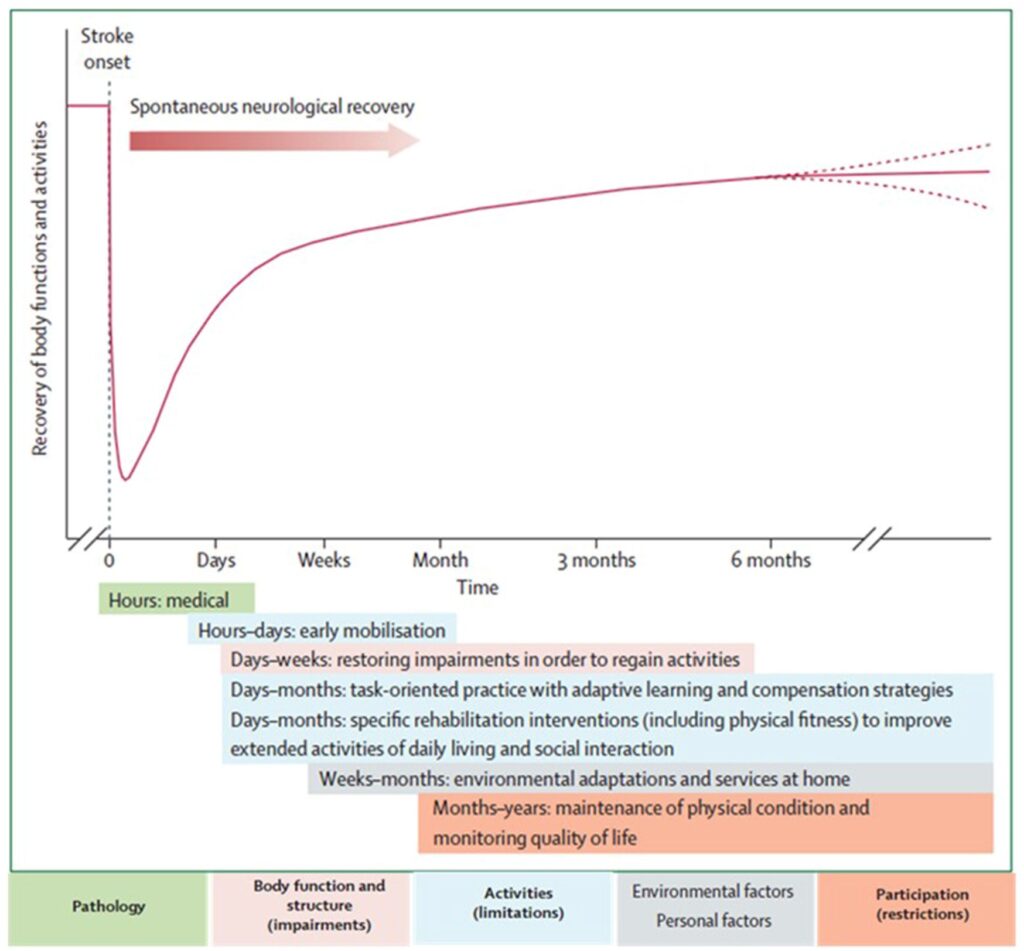

As your brain begins to repair itself, and therapists help you, you will hopefully see larger-scale improvements. However, long-lasting balance problems may occur after discharge, especially if the stroke has affected your vision or hearing.

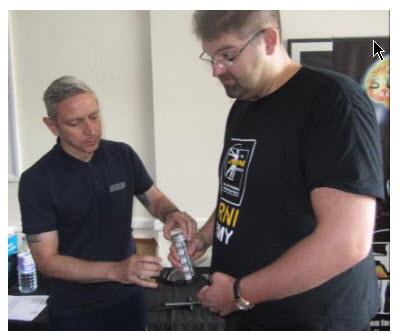

After discharge, with a therapist or trainer guiding and guarding you to extend your capabilities, rehabilitation can take many forms and should be supervised by a therapist or a specialist trainer who will provide individually-tailored activities to progressively stimulate your recovery.

You may find that this includes challenging types of weight bearing and weight-shifting. You may be starting by holding onto a fixed bar such a rail or banister (making sure to involve your more-affected upper limb in the way that your therapist or trainer will show you).

Balance perturbation and lower body strength training (again with a therapist or trainer guiding and guarding you to extend your capabilities) are identified as successful further training regimens.

Balance perturbation and lower body strength training (again with a therapist or trainer guiding and guarding you to extend your capabilities) are identified as successful further training regimens.

Multiple guided and guarded requirements for you to cope with gentle pushes, attempts to reach for objects away from your trunk can complement your balance control attempts.

It’s completely normal to feel worried or scared about carrying out any balance exercise. They are challenging and all retraining away from a seated position carries a risk of falling.

But it’s vital to continually extend your boundaries whilst minimising the risk to your safety. And it’s equally vital that you ask your therapist or specialist trainer how to do this.

When you start to take steps and are into the primary zone of controlling your gait again, there are so many ways you may find that a simple walking stick can improve your stability and confidence.

My caution would be to try not to rely fully a stick held in your less-affected hand so that it becomes habitual to weight-bear substantially though that side, thereby ‘negating the potential’ somewhat of your more-affected side. This can happen as a matter of course and can put back your recovery without you realising it.

TIP TO CONSIDER: try to reduce the use of a stick as much as possible when starting to move around the house again, in preparation for going outside with it. Then graduate towards leaving it at home or using it only when you’re out for longer stretches of time. Available for purchase is a handy stick which folds into three for this purpose. This can be carried and used if you’re tired.

To rehabilitate balance, a very simple rule seems to emerging from the sum of the latest evidence, which supersedes some of the historical accepted therapeutic advice for community rehab efforts: the more you attempt to move, the better your movement will get, not worse.

ANOTHER POINT TO CONSIDER: there are strong indications in the research that recovery of functional control after stroke occurs through strategic behavioural compensations plus what can be termed as ‘true recovery’ efforts rather than via processes of ‘true recovery’ efforts alone. Hence, an accumulation of some coping strategies that are most essential for your needs is a very good idea and can open a doorway to further levels of functional ability.

Passive or ‘correctional’ movement as a treatment option for most community survivors is being shown to be rather inferior to the stroke survivor being guided to make repeated, active attempts to complete tasks for themselves, ramping up the repetitions of tasks as much as is possible/is appropriate and as much as concomitant problems such as fatigue allow for.

So, some physical coping strategies (such as a quick technique for getting to your feet from seated without help or a lying position on the floor without help) are much better to have learned quickly via training to enable you to progress, rather than to be stuck without applicable techniques to perform them easily.

Other examples you can explore in Had a Stroke? Now What? can last you a lifetime. By retraining each one and making it part of your ‘repertoire’, you may also start noticing that they help you manage your (current) limitations and help you perform task specifics.

Other examples you can explore in Had a Stroke? Now What? can last you a lifetime. By retraining each one and making it part of your ‘repertoire’, you may also start noticing that they help you manage your (current) limitations and help you perform task specifics.

And some coping strategies are absolutely fit for purpose therefore and can be retained as useful, but many can be minimised and ideally negated as you gain more control and strength. They can be regarded as ‘facilitators’ which can help you to self-manage.

You’ll most probably ‘souvenirs’ from your stroke, but nevertheless, you need to get yourself into the ‘success zone’ fast in order to try to counteract their effects.

For optimal recovery, you need helpful interim strategies which can minimise the chances of any damage (from balance loss, for instance) that can occur whilst pushing yourself forward to deal with situations you’ll find yourself in during daily life.

You can also find lots of these in the ARNI 7 stroke rehab training video set, available in DVD or online anytime viewing.

When people have strokes, loss of strength as a result can be extensive and a major contributor to prolonged recovery times. It’s estimated that the strength loss after the stroke is around 50% on the affected side of the body. The reasons for losing strength are related to factors such as weak neural activity after a brain injury and losing muscle mass (atrophy).

When people have strokes, loss of strength as a result can be extensive and a major contributor to prolonged recovery times. It’s estimated that the strength loss after the stroke is around 50% on the affected side of the body. The reasons for losing strength are related to factors such as weak neural activity after a brain injury and losing muscle mass (atrophy).

For example, by the severity of your difficulties and perceived losses, your individual coping style, your familial/social support network, your cultural beliefs about disability, and your previous mental-health.

For example, by the severity of your difficulties and perceived losses, your individual coping style, your familial/social support network, your cultural beliefs about disability, and your previous mental-health. For example, it may be best to avoid crowds and stressful conditions, which may in turn make you feel overwhelmed. You can try learning relaxation techniques to help you combat any stress and fatigue you may experience after your stroke. There are lots of devices and apps to help you manage to bring emotions to an equilibrium over time.

For example, it may be best to avoid crowds and stressful conditions, which may in turn make you feel overwhelmed. You can try learning relaxation techniques to help you combat any stress and fatigue you may experience after your stroke. There are lots of devices and apps to help you manage to bring emotions to an equilibrium over time.

Apathy can have negative impact on your recovery of function, your ADLs, general health, and quality of life. It can stop you from enjoying your social connections and bothering to do things that you enjoy. If you develop apathy, it can also lead to a significant extra burden for your families, carers and friends… and worries them because it’s obvious how it will hold you back from potentially conquering/coping better w the situation you’re in.

Apathy can have negative impact on your recovery of function, your ADLs, general health, and quality of life. It can stop you from enjoying your social connections and bothering to do things that you enjoy. If you develop apathy, it can also lead to a significant extra burden for your families, carers and friends… and worries them because it’s obvious how it will hold you back from potentially conquering/coping better w the situation you’re in. It can be easy to think that emotional changes will never improve, but research shows that you may well come to terms with the after-effects of your stroke, which may in turn help responses and mood to become more balanced.

It can be easy to think that emotional changes will never improve, but research shows that you may well come to terms with the after-effects of your stroke, which may in turn help responses and mood to become more balanced. These are most likely to be experienced by those working with families and carers working with survivors with significant cognitive, communication and physical difficulties. Behaviours can range in severity and most usually have a function such as communicating a frustrated or unmet need. Families and carers have to come to understand these behaviours as best as they can.

These are most likely to be experienced by those working with families and carers working with survivors with significant cognitive, communication and physical difficulties. Behaviours can range in severity and most usually have a function such as communicating a frustrated or unmet need. Families and carers have to come to understand these behaviours as best as they can. Consistent and positive support, such as that offered by an excellent therapist/trainer (a qualified ARNI Instructor being just one example) is a great way to start this, as such a person will come in to the home, offering an encouraging example of health and strength for the survivor to hopefully be motivated by, and will know many innovative strategies to trial with the person to help them be creative with their own recoveries.

Consistent and positive support, such as that offered by an excellent therapist/trainer (a qualified ARNI Instructor being just one example) is a great way to start this, as such a person will come in to the home, offering an encouraging example of health and strength for the survivor to hopefully be motivated by, and will know many innovative strategies to trial with the person to help them be creative with their own recoveries.

But you must also appreciate that a gradient of significant possible responsiveness to treatment (and also responsiveness to neglect of rehab/retraining) that extends after 12 months post-stroke has been uncovered, which is VERY relevant for the majority of stroke patients.

But you must also appreciate that a gradient of significant possible responsiveness to treatment (and also responsiveness to neglect of rehab/retraining) that extends after 12 months post-stroke has been uncovered, which is VERY relevant for the majority of stroke patients. To help with task-training, strength training and developing physical coping (not compensation) strategies, there are also so many adjuncts to community stroke rehab retraining these days – low tech to high tech – from AFO’s that can phase you on from rigid plastic orthotics, to upper limb de-weighting devices, simple and cost-effective devices like the

To help with task-training, strength training and developing physical coping (not compensation) strategies, there are also so many adjuncts to community stroke rehab retraining these days – low tech to high tech – from AFO’s that can phase you on from rigid plastic orthotics, to upper limb de-weighting devices, simple and cost-effective devices like the

Working with more than 100 therapists (occupational therapists and physiotherapists) and 200 stroke patients,

Working with more than 100 therapists (occupational therapists and physiotherapists) and 200 stroke patients, This platform includes a smartwatch app with tailored coaching to help people own their rehabilitation journey and inform their clinicians on their progress. The smartwatch app works like a step counter, it tracks minutes of arm activity through an algorithm developed for stroke survivors.

This platform includes a smartwatch app with tailored coaching to help people own their rehabilitation journey and inform their clinicians on their progress. The smartwatch app works like a step counter, it tracks minutes of arm activity through an algorithm developed for stroke survivors. This will involve wearing wrist-based sensors and motion trackers during a 2 hour session at Imperial’s White City Campus to carry out tasks of daily activities such as using a knife and fork, reading a book and more.

This will involve wearing wrist-based sensors and motion trackers during a 2 hour session at Imperial’s White City Campus to carry out tasks of daily activities such as using a knife and fork, reading a book and more.

Please fill in this expression of interest form:

Please fill in this expression of interest form:

Rehabilitation after stroke is a partnership between you and your ARNI instructor or therapist. You’ll know that regular practice of techniques and exercises is necessary to optimise progress after stroke, but during the times that your Instructor isn’t present, these may or may not be difficult to perform.

Rehabilitation after stroke is a partnership between you and your ARNI instructor or therapist. You’ll know that regular practice of techniques and exercises is necessary to optimise progress after stroke, but during the times that your Instructor isn’t present, these may or may not be difficult to perform. Currently there is no stroke specific measurement tool available to do this. This study aims to address this gap in stroke rehabilitation.

Currently there is no stroke specific measurement tool available to do this. This study aims to address this gap in stroke rehabilitation.  If you have any questions, please contact Dylan Kerr (

If you have any questions, please contact Dylan Kerr (

Tiredness is something we all experience in our everyday lives. But how about the sort of tiredness which seems to be unrelated to physical or mental exertion, and does not seem to be alleviated by rest? This is a real problem for many stroke survivors on top of the many other problems they may face – and is called ‘fatigue’.

Tiredness is something we all experience in our everyday lives. But how about the sort of tiredness which seems to be unrelated to physical or mental exertion, and does not seem to be alleviated by rest? This is a real problem for many stroke survivors on top of the many other problems they may face – and is called ‘fatigue’. The Effort Lab, led by

The Effort Lab, led by  It takes no more than 45 minutes on an online combined quiz and questionnaire:

It takes no more than 45 minutes on an online combined quiz and questionnaire:

Strong evidence exists that physiotherapy improves the ability of people to move and be independent after suffering a stroke. But at six months after stroke, we know that many people remain unable to produce the movement needed for every-day activities such as answering a telephone. So, what can be done?

Strong evidence exists that physiotherapy improves the ability of people to move and be independent after suffering a stroke. But at six months after stroke, we know that many people remain unable to produce the movement needed for every-day activities such as answering a telephone. So, what can be done? 2. Second, to optimise a physiotherapist’s chances to advise/work on an optimal combination of rehab interventions for each individual after stroke, it would be ideal to find out what kinds of sleep patterns are most beneficial for them.

2. Second, to optimise a physiotherapist’s chances to advise/work on an optimal combination of rehab interventions for each individual after stroke, it would be ideal to find out what kinds of sleep patterns are most beneficial for them. Ideally, more portable equipment should also be able to be accessed by therapists, which would cost less and is designed for use in small spaces. But such equipment would have to also be sensitive enough to provide meaningful feedback for therapists in a similar way to those used by the specialist labs. Such feedback could then be very useful for therapists and survivors to create optimal rehab plans together which would really enable the survivor to work on his/her edges of current ability.

Ideally, more portable equipment should also be able to be accessed by therapists, which would cost less and is designed for use in small spaces. But such equipment would have to also be sensitive enough to provide meaningful feedback for therapists in a similar way to those used by the specialist labs. Such feedback could then be very useful for therapists and survivors to create optimal rehab plans together which would really enable the survivor to work on his/her edges of current ability. A School of Health Sciences research team at the University of East Anglia (UEA) headed up by

A School of Health Sciences research team at the University of East Anglia (UEA) headed up by

Go for it if you can/if it’s appropriate for you!

Go for it if you can/if it’s appropriate for you!

They’ll then place reflective markers on your skin. These markers are tracked by infra-red cameras placed at the top of the walls of the MoveExLab.

They’ll then place reflective markers on your skin. These markers are tracked by infra-red cameras placed at the top of the walls of the MoveExLab.

You can bet that I’ve met quite a few stroke survivors over the years who’ve become prone to anxiety, depression and/or

You can bet that I’ve met quite a few stroke survivors over the years who’ve become prone to anxiety, depression and/or  I hope that I’ve been able to facilitate at least some of these people towards the benefits of maintaining a ‘growth mindset’ concerning their recovery, despite their difficulties.

I hope that I’ve been able to facilitate at least some of these people towards the benefits of maintaining a ‘growth mindset’ concerning their recovery, despite their difficulties.

Do MORE than able bodied people training-wise. Show them up!! Make them wish they WERE YOU!!

Do MORE than able bodied people training-wise. Show them up!! Make them wish they WERE YOU!!