As a stroke survivor, you probably heard the term ‘goal setting’ from your multi-disciplinary team who helped you in ‘the early days’. This is because goal setting is considered ‘best practice’ in clinical stroke rehabilitation and its benefits are well recognised. Let’s have a look now about how to translate this practice into something that you can do by yourself when you get home, by yourself or with collaboration from a family member or friend.,

First, it is recognised that even though goal setting is embedded within community-based stroke rehabilitation given by NHS, practice does vary and is potentially sub-optimal. Further, to date, few randomised controlled trials have been completed to demonstrate that goal setting makes a unique contribution to stroke survivors’ rehabilitation outcomes.

First, it is recognised that even though goal setting is embedded within community-based stroke rehabilitation given by NHS, practice does vary and is potentially sub-optimal. Further, to date, few randomised controlled trials have been completed to demonstrate that goal setting makes a unique contribution to stroke survivors’ rehabilitation outcomes.

You have received 6 weeks of community therapy, or you may have had much more, but many people after stroke feel that therapy ended much quicker than you may have liked. And if this therapy is now in the past, you will may possibly feel that it hasn’t optimally prepared you to try and haul yourself through the aftermath of stroke: ie, coping and trying to flourish as a stroke survivor, minimising multiple physical and psychological problems you may have been left with.

Unsurprisingly, a common denominator of many stroke survivors is that they believe (important to stress ‘believe’) that they have not been shown how to rehabilitate themselves effectively going forward.

Most usually understand that they need to ‘retrain’ themselves somehow, and are keen to go for it. And their supporters are keen to help them achieve their goals. But the same people hit a common wall, because they cast about in vain to find the best single way forward. It can take years for stroke survivors to exhaust presented (often very expensive) options, not realising that they had considerable power all that time to change their ‘status quo’, by planning and working out how to deliver self-set goals.

Often, not easy to do – but not particularly difficult either. Where does this leave ‘goals’? Will those things that the multi-disciplinary teams agreed with you to achieve in the community be the same kind of things you need to work out in the ‘real world’ and tackle as you move further away from from your time of stroke?

Often, not easy to do – but not particularly difficult either. Where does this leave ‘goals’? Will those things that the multi-disciplinary teams agreed with you to achieve in the community be the same kind of things you need to work out in the ‘real world’ and tackle as you move further away from from your time of stroke?

And how are goals supposed to be set and stuck to without that ‘negotiationary’ aspect to the process that the therapists helped you with in hospital and during community therapy?

All reasonable questions – let’s break it down to component parts:

Overall, most stroke survivors want to ‘normalise and de-medicalise’ their lives again. They can set goals to do this.

Goals are things you would like to achieve. Many stroke survivors will want to restore lost function, and be able to do the things that they could do before their stroke. These are broad aims that may seem unachievable, and they may not know how to start, but defining goals can help then to break these aims down into smaller, more achievable goals.

Goal setting involves some planning and thought, but usually does not take overly long to do. It basically provides you with the steps to move from where you are now, to where you want to be. You’ll find it to be an empowering process, giving you the chance to take control of your rehabilitation.

To do this, you’re going to ‘get specific’ and ALSO ‘get broad’. Stroke survivors often have very individual hopes for the here and now, and also for the future, in terms of the goals they would like to achieve.

So. once all your therapy finishes, how do you do it? All good questions. To find out the answer, let’s get back to basics.

Where to start.

1 – Identify your goals!

When thinking about goal setting, the first thing to do is identify your goals, ask yourself ‘What do I want to achieve?’

When setting personal goals, specificity is king. For example, just challenging yourself to “do more work” is way too vague, as you’ve got no way of tracking your progress, and no endpoint. Simply put, if your goals aren’t quantifiable, achieving success can be challenging.

When setting personal goals, specificity is king. For example, just challenging yourself to “do more work” is way too vague, as you’ve got no way of tracking your progress, and no endpoint. Simply put, if your goals aren’t quantifiable, achieving success can be challenging.

SMART goals can the answer, as you can break them down into five quantifiable factors.

Try and look at goals in this way: they should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic/results-based/relevant and timely (SMART). These specific goals should be meaningful to you, and be a mix of highly achievable and reasonable. That said, its good to throw a few unlikely ones in to the mix, which you can do your best at achieving.

Include short-term, mid-term and longer-term goals. Rehabilitation is a journey and takes time. Your goals will reflect this.

By the way, goals that move you forward are almost ALWAYS ABOUT YOU.. DOING THINGS. Not THINGS BEING DONE UNTO YOU.

And in the meantime so much can happen or, in particular, not happen.

Let me stress that you don’t have to become fanatical to achieve success in stroke recovery. Many stroke survivors are living day to day feeling frustrated with their lot. But frustration doesn’t negate intrinsic motivation. This motivation is drive you stimulation/drive you to start, and persevere.

Here some examples of common goals;

Here some examples of common goals;

- To walk indoors independently

- To walk upstairs safely using a hand rail

- To dress upper body independently, threading t shirt over weak arm

- To stand to pull up trousers

- To be able to cut a slice of bread

- To butter toast

- To manage independent exercise programme

To maintain range of movement in hand, wrist and elbow

To maintain range of movement in hand, wrist and elbow- To open a tablet bottle

- To remember when to take my tablets

- To know what my medication is for

- To get in and out of the car safely

- To be able to type an e-mail accurately

- To practice golf on a driving range

EXAMPLE: So, perhaps you would like to walk upstairs independently. Great! That might be a longer-term goal. First you must be able to stand with support. Then, you need to be able to lift one leg and support your weight with the other leg. Then you need to move yourself up a step. Review what you can do now and work from there. Stepping up could be a very difficult thing to do straight away, so your short-term goals might include specific exercises, for example marching, or squats, that strengthen the muscles that you need to climb the stairs. Once you have mastered this, you could increase the repetitions, or move on to stepping up to a low step. Then increase the height of the step, or the number of steps, and so on, until you complete the longer term goal of walking up stairs independently.

Whatever your personal goal, the trick is to break it down into smaller, achievable tasks.

Big Tips from Tom –

- Be ambitious but get someone to help you regulate your ambitiousness: in practice, ‘run it past someone who knows you well”,

- Reveal your limitations: if one of your primary goals is not to reveal your limitations for as many hours of the day as is possible, this can create an anti-risk paradigm towards your recuperation and self-training, it is highly unlikely you will do what it takes to progress.

Prioritise what you want to achieve. Hey, you don’t have to think about working out how to master everything at once… too many goals and trying to accomplish them is far too overwhelming and exhausting. Work out what you want to aim for first, and move to step 2.

2– Make a plan

Once you have identified your goals, you can start planning for their achievement and work out how to incorporate this into your routine.

Once you have identified your goals, you can start planning for their achievement and work out how to incorporate this into your routine.

How will you measure your progress, and over what time-scale? For example, you decide to master a few smaller steps before reaching for the staircase. But, how will you know when to move onto the next challenge? You might get bored with stepping up a few steps, and run the risk of becoming disheartened or become content to just do that, losing sight of your original longer-term goal. Instead, your goal could be to step up 10 small steps after 4 weeks. This is a time-specific and measurable goal. It keeps you focused and gives you something specific to aim for.

When you can measure goals, you can appreciate your progress, and this is so motivating! Thousands of people have found this very thing out after stroke. Just what you need to keep you moving forward.

Involve family, friends and carers. Their input is valuable, and you might want their help. They might think of things that you haven’t thought of, or provide that supportive arm, and it can helpful to get their perspective. They will be part of your journey. Time to start on that journey – move to Step 3.

3 – Do it!

Armed with your planner – do your ‘retraining’, practising formally and also by simply doing activities of daily-life. Record what you’re doing. Don’t overload yourself, but make sure you challenge yourself.

Armed with your planner – do your ‘retraining’, practising formally and also by simply doing activities of daily-life. Record what you’re doing. Don’t overload yourself, but make sure you challenge yourself.

A great tip for you would be: in retraining situations it is important to advance quickly toward practice of whole tasks with as much of the environment context made available as possible. For example, say, a goal of yours is to improve the action control of your paretic foot for being able to cope whilst walking outside, unsupervised and with no supports. The best retraining you can get is to ask a trainer or friend to plan a route for you to go with him or her, so that you can trial it safely and under careful supervision. You can work on leaving a stick behind or reducing the use of an AFO according to your current levels of ability.

A unifying similarity amongst successful stroke survivors is not cognitive or affective (relating to moods, feelings, and attitudes), but willingness to strive for goals deemed ‘unachievable’ for them by those around them (as worked out in your Steps 1 and 2).

CLICK PIC OF STROKE SURVIVOR DOING THE THREE PEAKS CHALLENGE WITH ONE OF OUR ARNI INSTRUCTORS, KIERON FRANKLIN FROM POOLE, WHO HAS TAKEN SOME OF HIS STROKE SURVIVORS ON THIS FOR THE LAST 2 YEARS. DONATE TO ‘MOUNTEMBER 2019‘ IF YOU’RE FEELING GENEROUS!

Tip – motivation is key – if you’re not intrinsically motivated, you’ll have no incentive to push beyond generally accepted boundaries.

4 – Review your goals regularly.

Life may take you in another direction, changing the attainability or suitability of your goals. You may be working towards them faster or slower than you anticipated, or may find that other goals have taken priority. Whatever is happening in your life, it is perfectly OK to adapt or change your goals to suit you where you are now.

Keep talking with the people close to you, try to stay positive and motivated. Also, help/guide others who are going through a similar experience, if you come into contact with them in person or online – this actually has an effect to keep YOU motivated…

5 – Identify barriers to effective goal setting, then adapt and overcome.

Barriers could include communication difficulties, cognitive impairment, fatigue, mood disorders, other health conditions and even a lack of knowledge or understanding of your problems/condition.

If you feel you may have these, or other barriers, don’t let it stop you setting your own goals.

If you feel you may have these, or other barriers, don’t let it stop you setting your own goals.

Take time to ensure that your goals are what you want to achieve. Try to enlist the support of positive people who will take the time to work through what you want to achieve, whether they are family or carers, or therapists/instructors. Positivity breeds positivity.

Be aware of your limitations, but almost everyone can improve and become more functional. Listen to your body and adapt your goals accordingly. You could just break them down to smaller tasks, or do them a different way.

If you are too fatigued, don’t struggle. Rest and return to the task more refreshed.

Educate yourself; there is a wealth of information available about stroke and self-help online and through books.

You can read more about goal setting in The Successful Stroke Survivor, as well as lots of innovative ways to encourage rehabilitation after stroke.

What if I need more help?

Working with a therapist or trainer can be really motivating. This collaboration combines your initiative and drive with the knowledge and experience of a professional. For example, ARNI instructors are specifically trained in methods of stroke rehabilitation and will work with you to identify goals that are functional and personal to you, and together you will strive to achieve them. Empowering you to take control of your rehabilitation.

CALL ARNI now on 0203 053 0111 or write in to receive an info pack through the post.

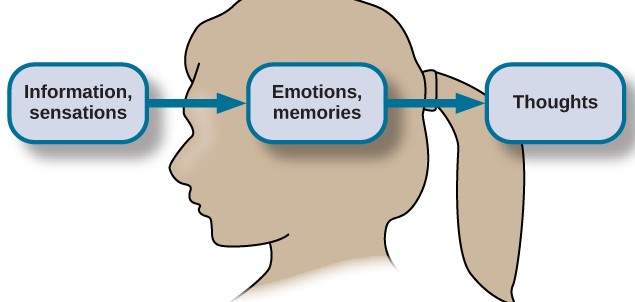

Put simply, cognition is thinking; it is the processing, organising and storing of information – an umbrella term for all of the mental processes used by your brain to carry you through the day, including perception, knowledge, problem-solving, judgement, language, and memory. The brain’s fantastic complexity means that it can collect vast amounts of information from your senses (sights, sounds, touch, etc) and combine it with stored information from your memory to create thoughts, guide physical actions, complete tasks and understand the world around you.

Put simply, cognition is thinking; it is the processing, organising and storing of information – an umbrella term for all of the mental processes used by your brain to carry you through the day, including perception, knowledge, problem-solving, judgement, language, and memory. The brain’s fantastic complexity means that it can collect vast amounts of information from your senses (sights, sounds, touch, etc) and combine it with stored information from your memory to create thoughts, guide physical actions, complete tasks and understand the world around you. A stroke can affect the way your brain understands, organises and stores information. This brain injury can result in damage to the areas of the brain that are responsible for perception, memory, association, planning, concentration, etc. The severity and localisation of the stroke will effect the type and level of difficulties experienced by an individual, and will vary from person to person.

A stroke can affect the way your brain understands, organises and stores information. This brain injury can result in damage to the areas of the brain that are responsible for perception, memory, association, planning, concentration, etc. The severity and localisation of the stroke will effect the type and level of difficulties experienced by an individual, and will vary from person to person.

To help with memory and perception problems, try using a diary, day planner, calendar or notepad. Writing down appointments and creating to-do-lists can help you to remember them.

To help with memory and perception problems, try using a diary, day planner, calendar or notepad. Writing down appointments and creating to-do-lists can help you to remember them. Being in a quiet room can also help you when reading or learning something new. Reducing visual distractions may also help you to concentrate. Keeping the area around you as clutter free as possible could help you to focus.

Being in a quiet room can also help you when reading or learning something new. Reducing visual distractions may also help you to concentrate. Keeping the area around you as clutter free as possible could help you to focus.

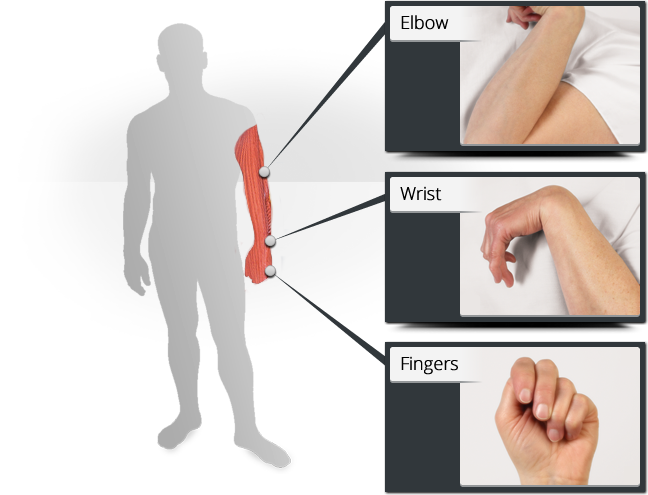

Muscle stiffness;

Muscle stiffness;

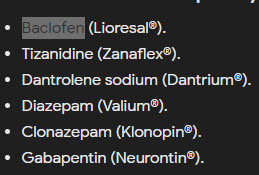

Examples of global (oral) medication are (trade names removed but see pic to the right), aim to relax your muscles by ‘turning down’ your nervous system. The downside of many of these is that they can also cause you to feel drowsy, confused, dizzy, weak, tired or to have a headache.

Examples of global (oral) medication are (trade names removed but see pic to the right), aim to relax your muscles by ‘turning down’ your nervous system. The downside of many of these is that they can also cause you to feel drowsy, confused, dizzy, weak, tired or to have a headache.

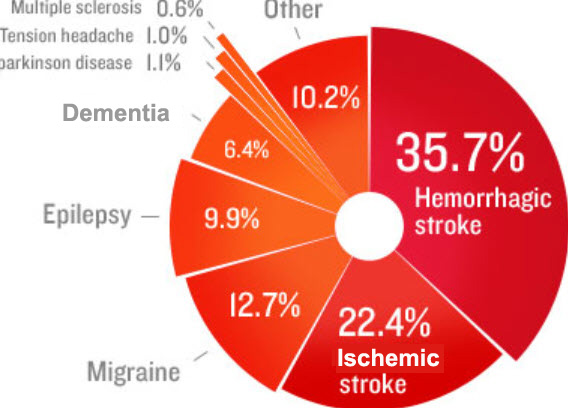

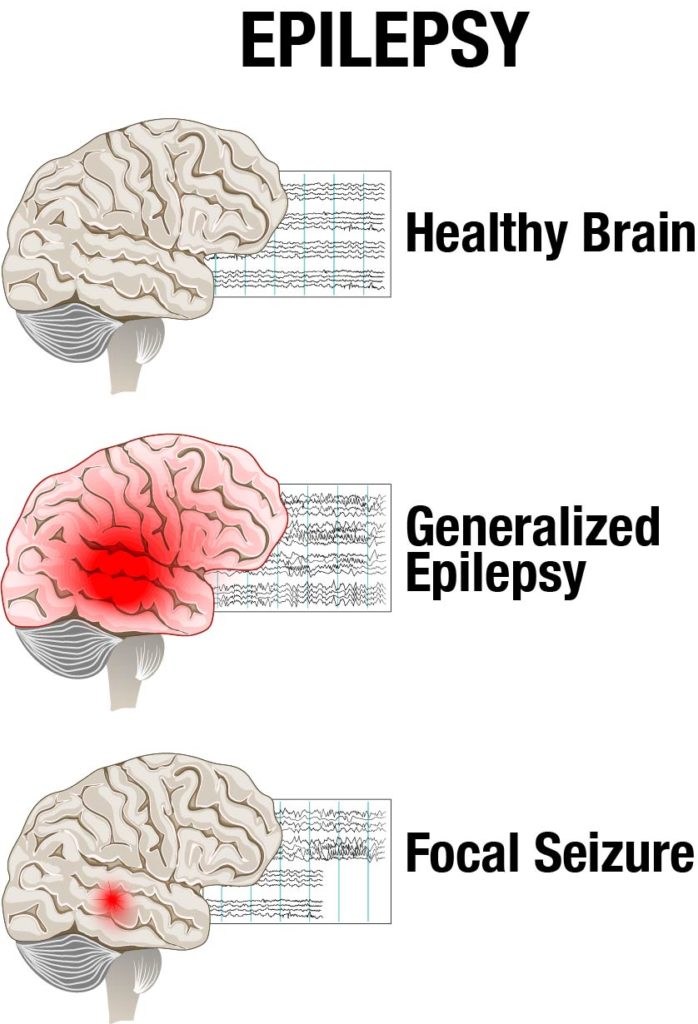

Stroke is one of many conditions that can lead to seizures, or epilepsy. You may think of these as ‘having fits’. In the UK this condition affects just under 1% of the population. Around 5% of people who have a stroke will have a seizure within the following few weeks. These are known as acute or onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke.

Stroke is one of many conditions that can lead to seizures, or epilepsy. You may think of these as ‘having fits’. In the UK this condition affects just under 1% of the population. Around 5% of people who have a stroke will have a seizure within the following few weeks. These are known as acute or onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. People can actually be taught to ‘ward off fits’! I learned the hard way how to do this. It’s a real trick of the trade you can use as a stroke survivor! Jut get in touch with me and I’ll tell you how I do it. 2004 was the last time I personally had a fit. I developed a 3-stage process which is remarkably successful. Part psychological and part-physical, it just works for me and might work for you too.

People can actually be taught to ‘ward off fits’! I learned the hard way how to do this. It’s a real trick of the trade you can use as a stroke survivor! Jut get in touch with me and I’ll tell you how I do it. 2004 was the last time I personally had a fit. I developed a 3-stage process which is remarkably successful. Part psychological and part-physical, it just works for me and might work for you too.  Anti-epileptic medications (AEDs) work by preventing excessive build-up of electrical activity in the brain, which is causing the seizures. Unfortunately, the normal activity of the brain can be affected, leading to drowsiness, dizziness, and confusion amongst other side effects. Once your body is used to the medication, these side effects may disappear.

Anti-epileptic medications (AEDs) work by preventing excessive build-up of electrical activity in the brain, which is causing the seizures. Unfortunately, the normal activity of the brain can be affected, leading to drowsiness, dizziness, and confusion amongst other side effects. Once your body is used to the medication, these side effects may disappear.

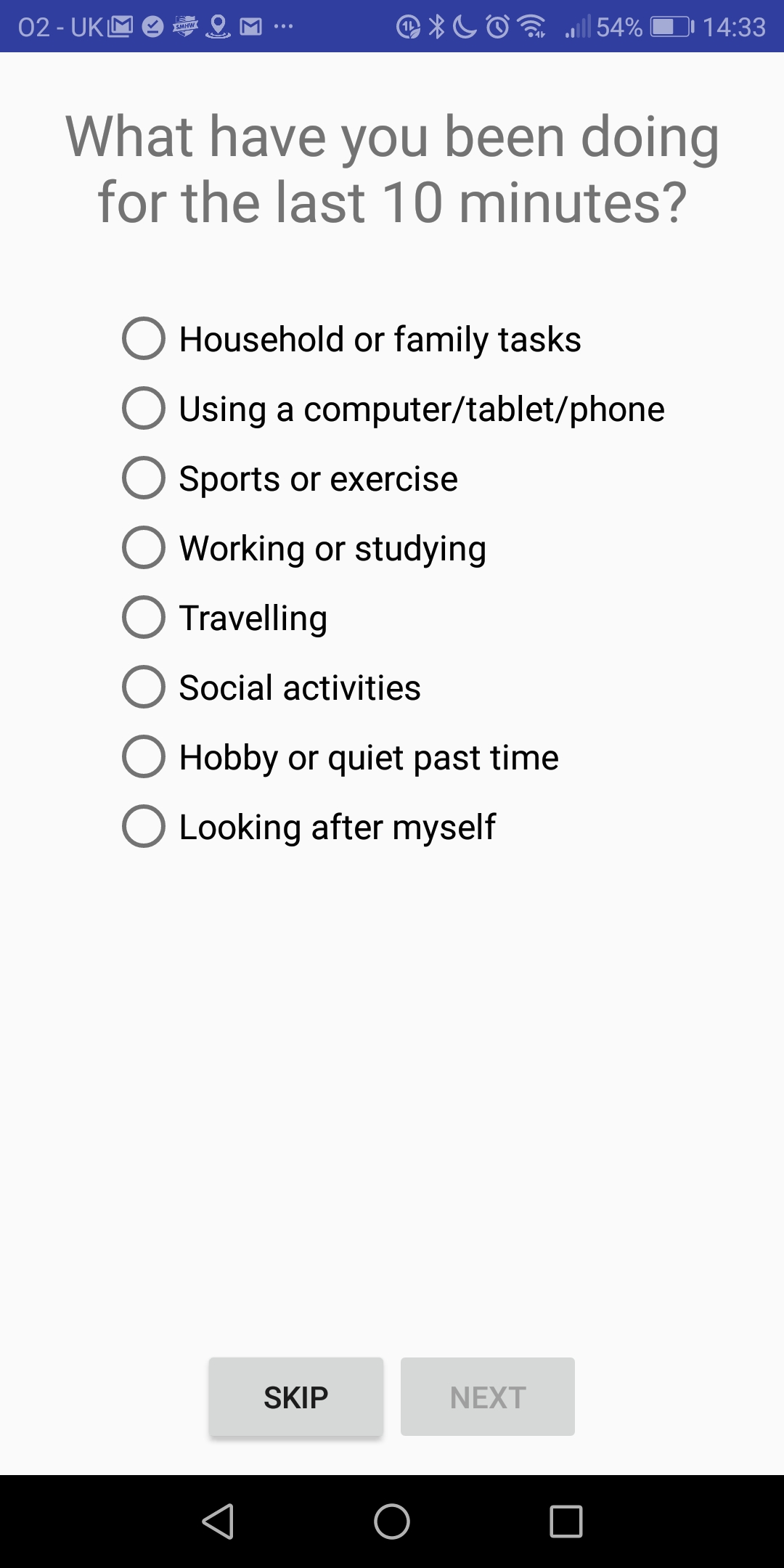

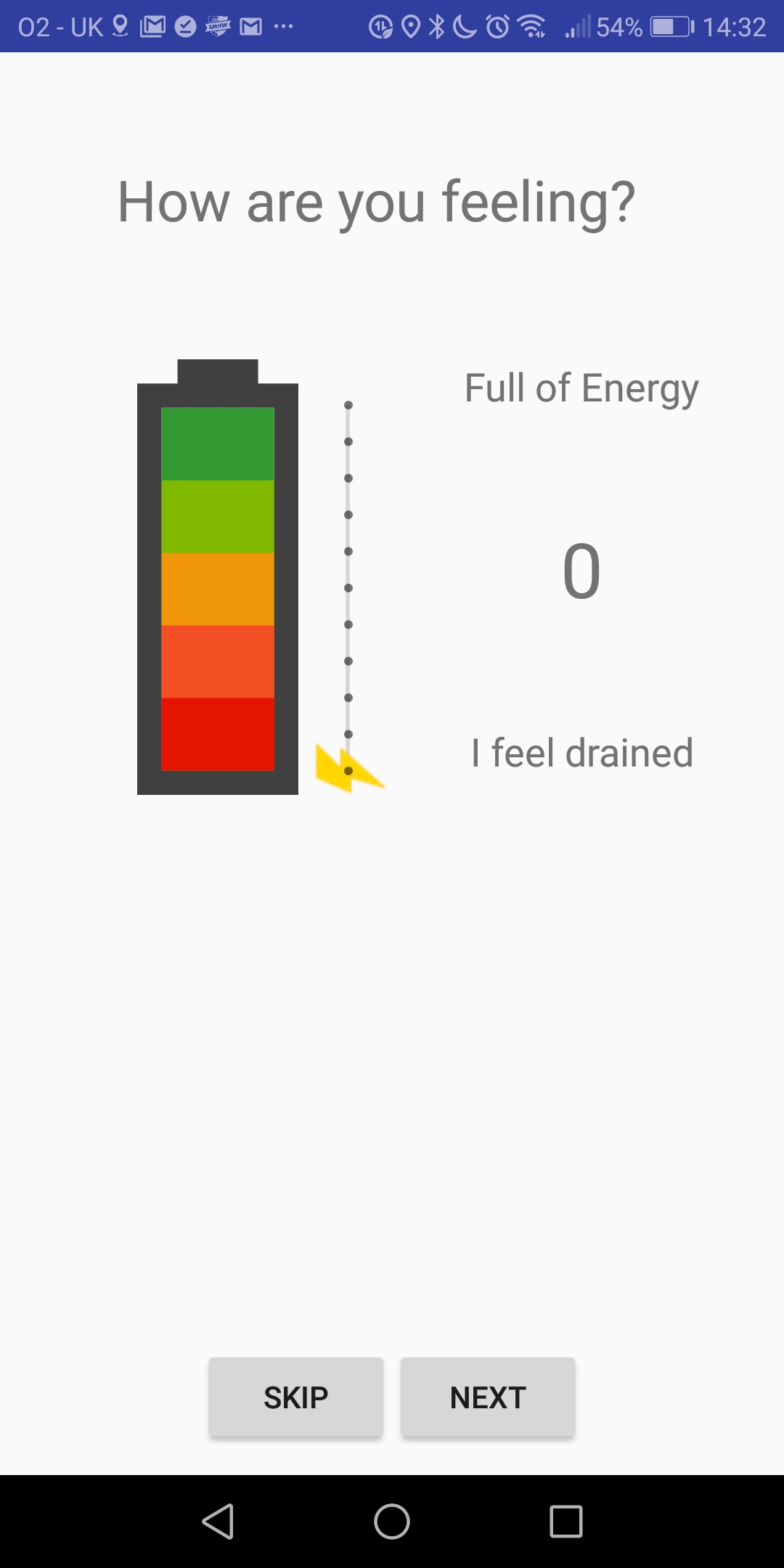

Fatigue is often experienced after acquired brain injury and people often try to manage via fatigue strategies such as planning and pacing. In order to use such strategies, the individual needs to build a picture of how their fatigue affects them in daily life. Usually, a daily diary sheet of sleep, rest, activity and fatigue is completed. Apps on smart phones are able to collect “in the moment” information about people’s fatigue experiences and to collect information about sleep and rest patterns. This information could help the person with brain injury, their carers and their therapists to learn about their fatigue more effectively, and identify triggers and patterns of fatigue.

Fatigue is often experienced after acquired brain injury and people often try to manage via fatigue strategies such as planning and pacing. In order to use such strategies, the individual needs to build a picture of how their fatigue affects them in daily life. Usually, a daily diary sheet of sleep, rest, activity and fatigue is completed. Apps on smart phones are able to collect “in the moment” information about people’s fatigue experiences and to collect information about sleep and rest patterns. This information could help the person with brain injury, their carers and their therapists to learn about their fatigue more effectively, and identify triggers and patterns of fatigue. A student researcher conducting his doctorate at Oxford Brookes University has developed an early prototype of an app, based on interviews with people with brain injury. This app works on android mobile phones and asks the user (who has experienced a stroke or other brain injury) to rate their fatigue, identify what they were doing at the time… and to complete a reaction time test.

A student researcher conducting his doctorate at Oxford Brookes University has developed an early prototype of an app, based on interviews with people with brain injury. This app works on android mobile phones and asks the user (who has experienced a stroke or other brain injury) to rate their fatigue, identify what they were doing at the time… and to complete a reaction time test.

If you’re a current patient reading this, both are about to become your best friends. They are also going to be pushing you hard. This is for a very good reason however. They are going to get you moving. Focusing mainly on your physical rehabilitation, physiotherapists and occupational therapists usually build custom plans to fit these needs.

If you’re a current patient reading this, both are about to become your best friends. They are also going to be pushing you hard. This is for a very good reason however. They are going to get you moving. Focusing mainly on your physical rehabilitation, physiotherapists and occupational therapists usually build custom plans to fit these needs.  Physiotherapy begins with the most basic tasks and movements, with the aim of protecting your more-affected side from injury. These gradually progress to exercises and tasks that aim to improve your balance, help you relearn basic coordination skills and functional tasks such as successfully handling objects and walking. During this time, what’s your overall mission to be? The answer is ‘everything you humanly can’. Along with post-stroke weakness in one or more limbs, stroke survivors of all ages frequently are de-conditioned as a result of immobility, fatigued on a daily basis and often have insufficient underlying motor activity to start the kind of task-related practice they need to do, which does make everything much harder.

Physiotherapy begins with the most basic tasks and movements, with the aim of protecting your more-affected side from injury. These gradually progress to exercises and tasks that aim to improve your balance, help you relearn basic coordination skills and functional tasks such as successfully handling objects and walking. During this time, what’s your overall mission to be? The answer is ‘everything you humanly can’. Along with post-stroke weakness in one or more limbs, stroke survivors of all ages frequently are de-conditioned as a result of immobility, fatigued on a daily basis and often have insufficient underlying motor activity to start the kind of task-related practice they need to do, which does make everything much harder. Survivors are noted to be inactive (and alone, in therapy terms) for much of the day as inpatients. This is time that is acknowledged by

Survivors are noted to be inactive (and alone, in therapy terms) for much of the day as inpatients. This is time that is acknowledged by  good thing to do so – it may not be, depending on daily presentation) that will be in play. One thing stands out from the evidence: that it has been shown that family participation in exercise routines for stroke patients empowers the caregiver’s help and may reduce their stress levels. Which is definitely a good thing. Making family members, carers and friends feel they are useful and contributing to the process is good.

good thing to do so – it may not be, depending on daily presentation) that will be in play. One thing stands out from the evidence: that it has been shown that family participation in exercise routines for stroke patients empowers the caregiver’s help and may reduce their stress levels. Which is definitely a good thing. Making family members, carers and friends feel they are useful and contributing to the process is good.

Information provision remains a commonly reported unmet need in rehab. Stroke survivors and carers consistently report that they do not know enough about the mechanisms, cause, and consequence of stroke. It is difficult to know whether this is a true expression of lack of needed knowledge or a reflection of stroke survivors’ and carers’ continued post-stroke uncertainty. A

Information provision remains a commonly reported unmet need in rehab. Stroke survivors and carers consistently report that they do not know enough about the mechanisms, cause, and consequence of stroke. It is difficult to know whether this is a true expression of lack of needed knowledge or a reflection of stroke survivors’ and carers’ continued post-stroke uncertainty. A  Similarly for upper limb, perhaps

Similarly for upper limb, perhaps

Research into fatigue is at its very early stages. Work to contribute towards a treatment has now been spearheaded by Dr Anna Kuppuswamy, the lead researcher on the project.

Research into fatigue is at its very early stages. Work to contribute towards a treatment has now been spearheaded by Dr Anna Kuppuswamy, the lead researcher on the project.

Researchers at the University of Oxford are currently investigating how sleep is affected by stroke.

Researchers at the University of Oxford are currently investigating how sleep is affected by stroke. We know that sleep plays an important role in learning. Studies have shown that if you take two groups of people and teach them the same skill, such as juggling, then allow one group to sleep for a few hours and keep the other group awake, the sleep group will perform significantly better when retested as they have been able to consolidate the memories of learning the skill through sleep.

We know that sleep plays an important role in learning. Studies have shown that if you take two groups of people and teach them the same skill, such as juggling, then allow one group to sleep for a few hours and keep the other group awake, the sleep group will perform significantly better when retested as they have been able to consolidate the memories of learning the skill through sleep. The current study involves coming to a research centre in Oxford for one session to complete a couple of motor assessments with the upper limbs and to answer a couple of questionnaires about your sleep and mood. Then researchers will set you up with a pair of sleep monitoring wrist watches for you to wear for a week with a simple sleep diary asking what times you go to bed and get up each day.

The current study involves coming to a research centre in Oxford for one session to complete a couple of motor assessments with the upper limbs and to answer a couple of questionnaires about your sleep and mood. Then researchers will set you up with a pair of sleep monitoring wrist watches for you to wear for a week with a simple sleep diary asking what times you go to bed and get up each day. If you would like to join this study/find out more, please feel free to contact the researchers:

If you would like to join this study/find out more, please feel free to contact the researchers:

In the UK, stroke services are developing/referring in to stroke-specific community exercise programmes. The system is reasonably analogous to the very well-established rehabilitation services for cardiac disease patients which usually start after usual rehabilitation has ended.

In the UK, stroke services are developing/referring in to stroke-specific community exercise programmes. The system is reasonably analogous to the very well-established rehabilitation services for cardiac disease patients which usually start after usual rehabilitation has ended. ARNI offers group classes rarely, preferring to concentrate charitable efforts on getting instructors into people’s homes in order to provide that vital one to one rehabilitation support that can be achieved at lowest cost.

ARNI offers group classes rarely, preferring to concentrate charitable efforts on getting instructors into people’s homes in order to provide that vital one to one rehabilitation support that can be achieved at lowest cost. Exercise is a physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful. Physical activity includes any body movement that contracts your muscles to burn more calories than your body would normally do so just to exist at rest. Although learning to enjoy and plan structured exercise into your routine would definitely improve fitness, it is not the only way to improve fitness. Activities of daily life keep your body moving and still count toward the recommended amount of weekly physical activity. Most importantly, no matter what your current fitness level, you are able to improve your physical fitness and therefore, your heart health, by increasing physical activity and/or exercise as you are able.

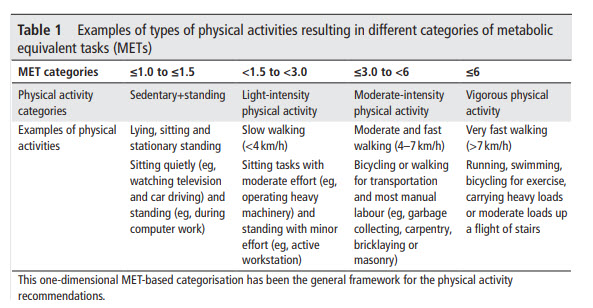

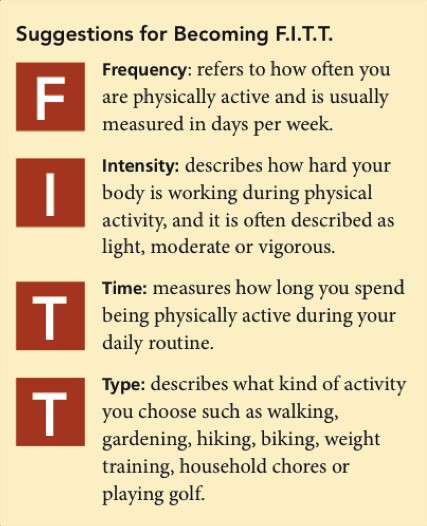

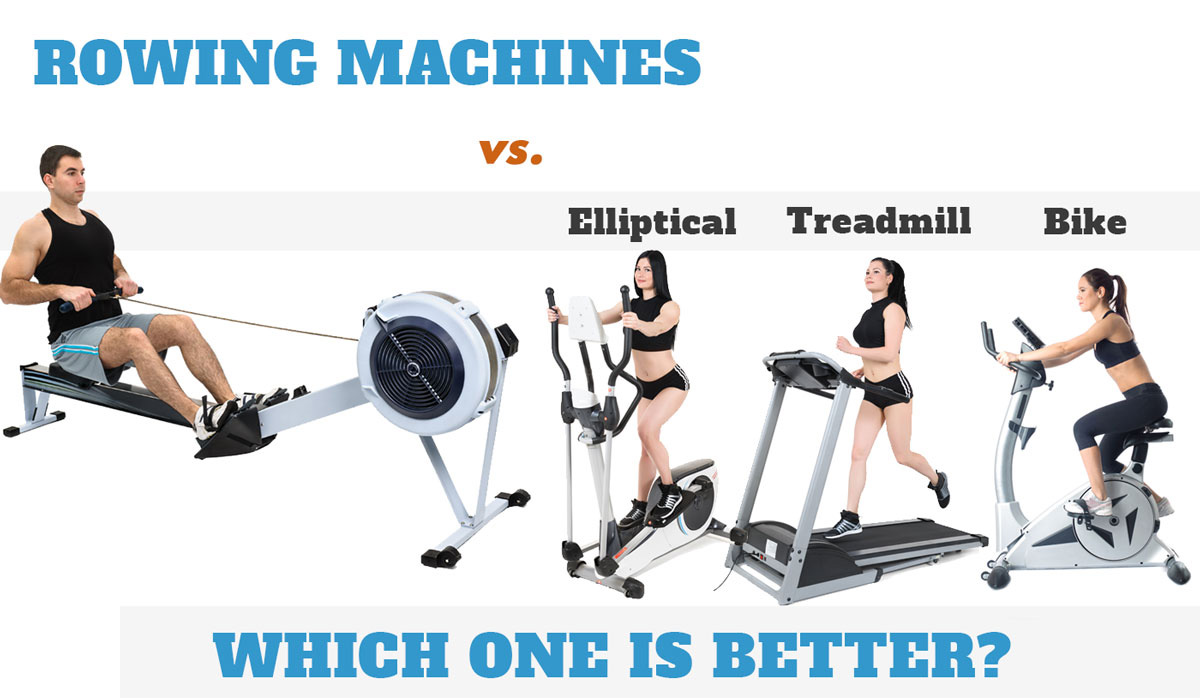

Exercise is a physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful. Physical activity includes any body movement that contracts your muscles to burn more calories than your body would normally do so just to exist at rest. Although learning to enjoy and plan structured exercise into your routine would definitely improve fitness, it is not the only way to improve fitness. Activities of daily life keep your body moving and still count toward the recommended amount of weekly physical activity. Most importantly, no matter what your current fitness level, you are able to improve your physical fitness and therefore, your heart health, by increasing physical activity and/or exercise as you are able. Cardiovascular exercise covers everything from walking, jogging or running over-ground or on a treadmill (with or without bodyweight support such as the Alter-G anti-gravity treadmill), to cycling, recumbent stepping or swimming. Many people call it ‘cardio’ exercise.

Cardiovascular exercise covers everything from walking, jogging or running over-ground or on a treadmill (with or without bodyweight support such as the Alter-G anti-gravity treadmill), to cycling, recumbent stepping or swimming. Many people call it ‘cardio’ exercise.

In terms of your arteries, aerobic exercise decreases what is called arterial stiffness, this allows for the blood to be pushed along the arteries through proper dilation and contractibility, with an adequate amount of pressure.

In terms of your arteries, aerobic exercise decreases what is called arterial stiffness, this allows for the blood to be pushed along the arteries through proper dilation and contractibility, with an adequate amount of pressure. Intensity of exercise is dependent on your heart rate or the amount of effort you feel you are exerting. To determine how ‘hard’ your heart is working and the intensity during exercise is also depended on your age. The more intense the activity the higher your heart rate will be. You might hear the phrase Rate of Perceived Exertion or RPE for short.

Intensity of exercise is dependent on your heart rate or the amount of effort you feel you are exerting. To determine how ‘hard’ your heart is working and the intensity during exercise is also depended on your age. The more intense the activity the higher your heart rate will be. You might hear the phrase Rate of Perceived Exertion or RPE for short.

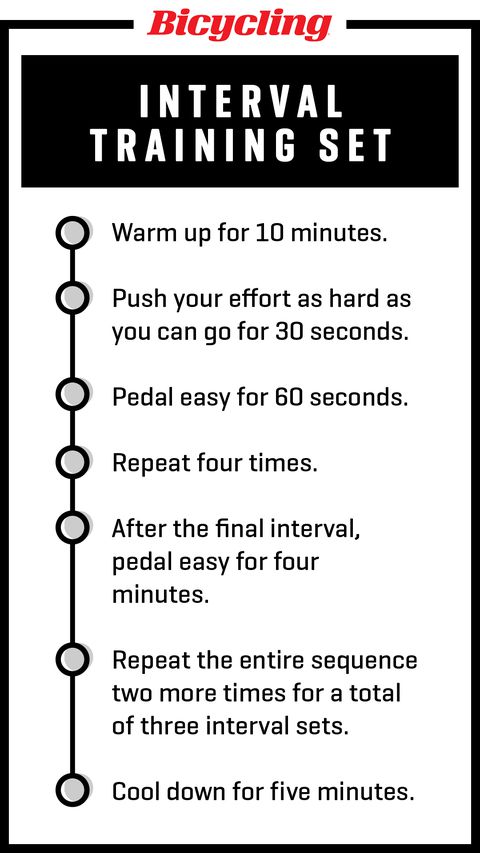

Cardio exercise. It’s a good idea to plan from the start, how you are going to get cardio exercise done by yourself at home. In the beginning you may be nervous about doing some exercise training at home without supervision, but if you’re smart about it you can do it safely and successfully.

Cardio exercise. It’s a good idea to plan from the start, how you are going to get cardio exercise done by yourself at home. In the beginning you may be nervous about doing some exercise training at home without supervision, but if you’re smart about it you can do it safely and successfully. I strongly advise the recumbent bicycle for stroke survivors with upper limb limitations – this solution is the best I’ve found.

I strongly advise the recumbent bicycle for stroke survivors with upper limb limitations – this solution is the best I’ve found.  A final point: it’s a good idea to monitor yourself while exercising, so you can follow your own progress and also know when you need to push yourself a little further. There are several ways you can do this. Heart rate monitors are a great way to keep track of the intensity you are working at. Speak with your GP to find out what heart rate you should be working at for your age.

A final point: it’s a good idea to monitor yourself while exercising, so you can follow your own progress and also know when you need to push yourself a little further. There are several ways you can do this. Heart rate monitors are a great way to keep track of the intensity you are working at. Speak with your GP to find out what heart rate you should be working at for your age. In terms of physical activity, I encourage you to incorporate a variety of exercises in to your lifestyle. Particularly things like getting out of your residence and walking as well as you can (accompanied as appropriate), swimming (swimming classes for stroke survivors are often available and run by some ARNI INSTRUCTORS) and are a great way to socialise while achieving something.

In terms of physical activity, I encourage you to incorporate a variety of exercises in to your lifestyle. Particularly things like getting out of your residence and walking as well as you can (accompanied as appropriate), swimming (swimming classes for stroke survivors are often available and run by some ARNI INSTRUCTORS) and are a great way to socialise while achieving something.

You might also want to buy some cards to support ARNI!

You might also want to buy some cards to support ARNI!